发布时间:2017年08月10日

* 欧阳辉教授指导的华为英文案例进入财新全球版最热门前三

本文由长江商学院欧阳辉教授和研究中心案例研究员李梦军完成。

相关内容如下,供大家学习:

For any communications equipment provider, the U.S. market cannot be ignored. As the birthplace of mobile communications, the United States has the greatest innovative capabilities and most stringent communications regulatory standards. It is still one of the strongest economies in the world, with large numbers of users and strong spending power. In a sense, if products are accepted by the U.S. market, they will also be accepted by the world market.

For Huawei, the American dream has been a long and arduous journey. It not only entails enterprise-level issues such as technology and capability, culture and communication, but also issues over industrial and political games. The communications industry often entwines with national security, resulting in an insurmountable barrier from American government’s supervision and obstruction. For U.S. operators, Huawei is a familiar but also unfamiliar name. And it seems a long way for them to understand and accept Huawei.

Early in 1999, Huawei set up a research institute in Dallas, specializing in developing products for the American market. In June 2001, Huawei established a wholly-owned subsidiary – Future Wei – in Texas, and began selling broadband and data products to local businesses. Just as in the European market, Huawei's advantage in the U.S. was cost effectiveness.

Huawei's advance in the U. S. market brought along doubts about its products. At the beginning of 2003, CISCO sued Huawei for violating its intellectual property in the Texas State Court. After a year and a half of patent disputes, the two sides finally reached a settlement. However, the dispute seriously affected Huawei's reputation, resulting in sluggish development of its business in the American market.

The joint venture founded by Huawei and 3Com played a critical role in the patent dispute with CISCO. This helped Huawei directly learn the significance of alliance strategies. Huawei then began to explore the international market by way of joint-venture models. It sought opportunities cooperating with the four major U.S. operators by joining hands with other counterparts.

In November 2003, the joint venture Huawei 3Com Communication Technology Co. Ltd. (H3C) was officially established. According to the agreement, data products would be sold in the H3C brand in the Chinese and Japanese markets, but in the 3Com brand in other markets. For Huawei, this global joint venture is of strategic importance. With the help of 3Com’s brand and global distribution channels, Huawei could offer OEM products at competitive prices for nearly 50,000 3Com channels in international markets. Since then, Huawei entered the U.S. market in a roundabout way.

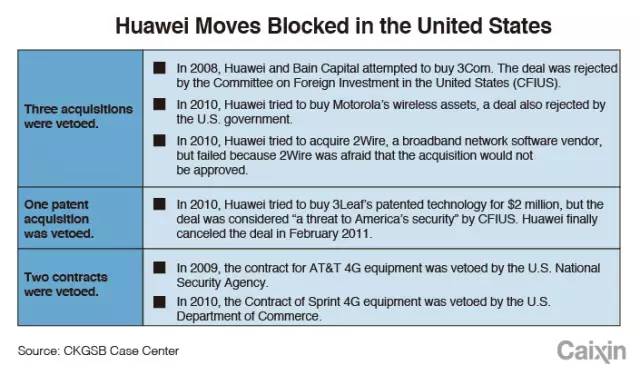

But because its business mainly served small- and midsized operators, Huawei has not yet signed a contract with any of the four major mobile operators (Verizon, ATT, Sprint and T-Mobile) which dominate the U.S. market. Huawei's strategy of opening the U. S. market by joint ventures also has produced few results. After 2008, Huawei tried to enter the U.S. through mergers and acquisitions, but was repeatedly blocked. Its landmark events are as follows:

At this stage, the U.S. government and CFIUS hardly gave Huawei any chance for direct access to the American market. The problem facing Huawei was acute. In 2011, the U.S. Congress launched an 18-month investigation into Huawei and ZTE. The U.S. House of Representatives Intelligence Committee released a report in 2012 and declared that Huawei and ZTE products were a threat to U.S. security, warning American telecom companies not to purchase Huawei and ZTE equipment.

Huawei's revenue from its business in the U.S. rose from $40 million in 2006 to $1.3 billion in 2011. (About $1.2 billion was from sales of smartphones, tablet PCs and similar devices). But this was minor compared to Huawei's 203.9 billion yuan (about $30 billion) of total revenue.

Huawei acquired 3Com for two reasons. First was Huawei’s need for a globalization strategy. After several years of exploring such a strategy, Huawei found it extremely difficult and expensive to establish its own brand in European, U.S. and other developed markets. As a modern network communication technology company, 3Com had good marketing channels and a large customer base. Through the acquisition, Huawei could quickly enter the U.S. market and increase its market share.

The second was Huawei’s need for strategic transformation. In order to adapt to the revolutionary changes taking place in the information industry, Huawei began to grow from a telecom operating network to an enterprise business and then to a consumer business. Huawei has long focused on the operator market. After completely withdrawing from H3C in February 2007 Huawei realized the importance of the enterprise market. The acquisition of 3Com just made up for Huawei losses in this market segment.

3Com was one of the founders of modern network communications technology, which was birthed in 1979. Affected by the internet bubble, 3Com's profit-margin declined in 1999 and resulted in a negative balance sheet. In 2000, 3Com lost its technological advantage in the high-end enterprise network-equipment market, and finally withdrew from the market. It then focused primarily on faster-growing businesses such as the consumer network business. By 2002, 3Com conducted large-scale global layoffs and shifted its focus to the China market.

On the eve of being acquired, 3Com entered financial distress. According to financial data disclosed on Sept. 20, 3Com’s sales were only $319 million and its losses reached $18.7 million in the first quarter of fiscal year 2008. Meanwhile, more than 30% of revenue and 95% of profits came from H3C, while H3C's revenue came mainly from Huawei. 3Com's operations were unsustainable.

On Sept. 28, 2007, Huawei teamed up with Bain Capital and announced an investment of $2.2 billion to bid for 3Com. Bain would hold 83.5% of 3Com’s shares, and Huawei 16.5%, with $363 million – in all-cash payment – via its wholly-owned subsidiary in Hong Kong. Huawei also reserved the right to increase its share by 5% in the future.

At first, 3Com agreed to the deal. Six months later, however, CFIUS blocked the deal on the grounds that it was a threat to the U.S. government's information security. Later, Bain was forced to back out of the deal, which was aborted. On Nov. 12, 2009, 3Com was bought by Hewlett-Packard for $2.7 billion.

The rise of American protectionism and the “China threat theory” are the main reasons for the failure of the merger and acquisition attempts. As a veteran telecom equipment provider, 3Com had been providing computer anti-intrusion detection equipment for the Pentagon and the U.S. Army and intelligence departments. Concerns over the threats that these critical computer networks could pose led the U.S. to come forward and block the acquisitions. Meanwhile, Huawei’s leader, Ren Zhengfei, a retired military veteran from China, exacerbated concerns among U.S. regulatory authorities.

Furthermore, Huawei's opaque management presented problems for regulators. As a fully independent unlisted private company – the only unlisted one in the Fortune Global 500 – Huawei had long taken a low-key gesture, avoiding media publicity, and refusing to publish its detailed shareholder structure, saying that its shares were held entirely by its staff. This was difficult for the U.S. government to permit.

Finally, Huawei's design for its 3COM deal also raised concern among regulators in the U.S. After the deal, Huawei held only 16.5% of H3C shares. In fact, it maintained a very close relationship with H3C in both personnel and business. For example, most H3C employees and 30% of its sales revenue came from Huawei. U.S. regulators worried that after the acquisition, Huawei's influence on 3COM would be more than was warranted from its shareholding percentage.

Despite all the obstacles in the past, Huawei is still trying to enter the U.S., but in different ways. Ren Zhengfei still places great hope on Huawei mobile phones entering the American market. He stressed in an internal speech that “the whole Huawei company can break the blockade of the United States only by making the frontline sharp. Otherwise, the company will remain so-so and will not break any blockade.”

Where will Huawei place its “sharp frontline”? And when will its American dream come true? This is not only an American dream for Huawei, but for many Chinese enterprises as well.

By Ouyang Hui and Li Mengjun

Li Mengjun is a research fellow of CKGSB Case Center.